As the proverb goes, from small beginnings come great things. With wires seemingly crossed, I was ready to give up on my interview with Mr Winner, author of Brilliant Orange, Stillness and Speed by Dennis Bergkamp and now #2Sides by Rio Ferdinand. I’d left the warmth of the Tricycle Theatre café and was about to enter Kilburn station when he called. Full of apologies, he asked if I’d had dinner. Ten minutes later, we were discussing Ronald Koeman’s Southampton team in an Afghan restaurant. Two hours later, I made my way back to the tube after an evening of lively football conversation with one of football’s most innovative writers and nicest men. Sadly, I only recorded about half an hour of our meal – here are the best bits:

As the proverb goes, from small beginnings come great things. With wires seemingly crossed, I was ready to give up on my interview with Mr Winner, author of Brilliant Orange, Stillness and Speed by Dennis Bergkamp and now #2Sides by Rio Ferdinand. I’d left the warmth of the Tricycle Theatre café and was about to enter Kilburn station when he called. Full of apologies, he asked if I’d had dinner. Ten minutes later, we were discussing Ronald Koeman’s Southampton team in an Afghan restaurant. Two hours later, I made my way back to the tube after an evening of lively football conversation with one of football’s most innovative writers and nicest men. Sadly, I only recorded about half an hour of our meal – here are the best bits:

Q. First things first, how did the project come about?

There were two other writers who were going to do it but for whatever reason, they couldn’t. Then in March, the publisher came to me and said ‘Can you do this in 3 months?’

Q. Had Rio read Stillness and Speed?

I’m not sure if he had or his people had, but they certainly knew of it. I guess that was the only reason to come to me, because I have no Manchester United connections and I didn’t know Rio. But it was nice that way. We have all of these silly prejudices as football fans, which is part of the fun but it also stops you seeing nice things. Talking with Rio every day and entering his mind was a bit like Stockholm Syndrome; you come to share their viewpoint. I started to feel very warmly towards United, when he spoke about Scholes and ‘Giggsy’. At one point I caught myself saying ‘Scholesy’ and I realised all of my Arsenal friends would actually disown me! When he spoke about Ferguson, I was seeing it through his eyes and I thought, yes, what a fantastic man. Not just a great manager, but a wonderful man. When it counted, he always did the right thing. To hear Rio’s view of Ferguson, you understand why he inspired his players. I rather love Ferguson now.

Q. How did the process work?

We did it mostly on the phone. We met initially, and there was one full day we had in Wilmslow, sat in the upstairs room of a pub, which was uncannily similar to the café in Holland where I used to talk to Dennis [Bergkamp]. But mostly we would speak on the phone while Rio was driving to training. He would drop his kids at school and then there was another half hour to Carrington. I’d know to stop when I could hear kids asking him for autographs.

Q. What was Rio like to work with?

He’s a very warm guy and I think he enjoyed the process. He’s rapidly maturing; you can see him growing before your eyes every time he’s on TV. He’s very outward-looking and he’s very curious about everything, not just football. He’s got his creative side with the magazine, his charity side (which is not just for show – it’s really important to him), and then there’s film, music, fashion. I don’t think he knows exactly what he’s going to do in the end but he’ll do something remarkable. There’s talk about him becoming the British representative for FIFA now, which would be very interesting. He’s very smart and very engaged in a nice way.

Q. The book feels very candid. Was there anything he didn’t want to discuss or asked to be removed?

He’s very open but there were a few things that he spoke about that he later decided he didn’t want to include for various reasons. One was a bit about a family holiday in Portugal with Anton and he wanted his brother to be a big part of the chapter. But when it was all done, Rio decided that with Anton back playing in England, he didn’t need any more shit. So everything Anton had said was either cut or put into Rio’s voice. There was also a bit of David Moyes stuff, a few unflattering observations and incidents that he wanted to cut out. He said he liked the guy and didn’t want to ‘cut his legs off’. Because it’s completely not a ‘settling scores’ book.

Q. Was it a conscious decision to avoid a traditional chronological approach?

There is a sort of rough chronology, in that it starts with childhood and ends with now. But in the middle of that, it can go anywhere. One of the things I hate about a lot of football biographies and autobiographies is that tedious structure where they start with some career highlight and then they just plod through the youth team, getting discovered, getting into the first team…It’s almost season by season and sometimes it’s just match reports. I can’t read them; I have a severe allergic reaction.

Rio had published a book eight years ago with a Sun journalist and it was done in a very skilful, ‘Sun’ way. Perhaps it was more accurate of who he was then, but he’s certainly not remotely like that now. So my pitch to Rio was ‘Look, I think there are all these different aspects of you and you’re not this tabloid character’. I told him to say whatever came into his head and think of it like scenes from a film; we wouldn’t know how it would all fit together until we had it all. He liked that approach. And the very first thing that he talked about was playing in the park with much older African guys, which turned out to be a perfect opening for the book.

I thought there would be more of a masterclass on the art of defending but that didn’t really develop. I had that experience with Dennis where he could break things down micro-second by micro-second and analyse from every angle, but I don’t think anyone else can do that.

Q. How did you find the ghostwriting process, compared to the biographer role for Stillness and Speed?

It’s much less work! With Dennis, it was a much more complicated process because there were lots of people to interview and I was sharing material with Jaap Visser, who was doing the Dutch version. With Rio, the main thing was to find the voice. He tells a lot of stories in reported speech but every time he speaks in the words of someone else, they all sound like Rio! So Fergie sounds like he grew up on an estate in Peckham, and so does Ronaldo. I couldn’t keep all of the distinctive parts of his speech but it was about taking the original style and making it flow better. When I took him a first, experimental chapter, Rio did a really clever thing. He read it aloud, and then said, ‘Yeah, that’s my voice’.

Once we’d agreed on the template, it was actually quite quick. I had about 25 hours of transcript and it was like a jigsaw puzzle, working out what could go with what to form a chapter. Then afterwards we worked out the order. At first, the publisher wanted to have a ‘juicy’ chapter first but Rio didn’t like that idea and neither did I. We wanted a book that reflected him accurately, in the same way that the Bergkamp book reflected Dennis very accurately. There, the idea was that he would play off other people in the same way that he did on the pitch. With Rio, he wanted to change his image and show he wasn’t just that guy who forgot the drugs test.

Buy #2Sides here

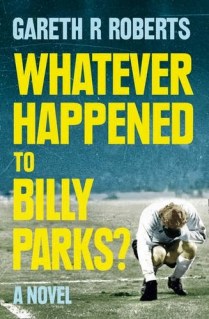

![whatever happened to billy parks[1]](https://ofpitchandpage.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/whatever-happened-to-billy-parks11.jpg?w=298&h=461) In the lofty world of fiction, few subjects are deemed as fatal as football. And I say that in 2014,nearly a decade after the success of David Peace’s The Damned United. The beautiful game, despite its inextricable ties to human nature and contemporary society, remains the source of exasperating literary pillory. But blessed be the few brave souls who fight the tide. This year, most notably Danny Rhodes took on memories of the Hillsborough disaster in Fan, and Gareth R Roberts inserted a fictional hero into the iconic world of 1960s West Ham United in What Ever Happened to Billy Parks? The former has been a much-heralded success; the latter won a prestigious Fiction Uncovered Award.

In the lofty world of fiction, few subjects are deemed as fatal as football. And I say that in 2014,nearly a decade after the success of David Peace’s The Damned United. The beautiful game, despite its inextricable ties to human nature and contemporary society, remains the source of exasperating literary pillory. But blessed be the few brave souls who fight the tide. This year, most notably Danny Rhodes took on memories of the Hillsborough disaster in Fan, and Gareth R Roberts inserted a fictional hero into the iconic world of 1960s West Ham United in What Ever Happened to Billy Parks? The former has been a much-heralded success; the latter won a prestigious Fiction Uncovered Award.